In the last couple of years, we’ve seen a number of disturbing news items about people being stopped at border crossings and their digital devices being searched. At the Chaos Communication Congress, Kurt Opsahl and William Budington of the Electronic Frontier Foundation broke down what is actually happening in this area. Here’s a recap of the talk with a dozen key facts and tips.

1. The agents don’t care about your privacy

Governments treat borders like especially dangerous areas and tend to assert more power and authority to conduct searches at borders than they do in the rest of the country.

It’s safe to assume that border agents in any country you visit follow policies or laws that allow them to search your digital devices. It’s also fair to assume they don’t care much about safeguarding your privacy. (In cases where such searches aren’t permitted, Opsahl and Budington, privacy advocates, didn’t speak highly of border agents’ adherence to the rules, either.)

What can happen if you refuse to give agents your passwords to facilitate their search? Border agents have enough power to make your life harder if you don’t comply. They can:

- Deny your entry if you are a visitor to the country (not if you’re a citizen or a permanent resident);

- Waste a lot of your time, potentially making you miss a connecting flight and wrecking your travel/business schedule;

- Seize your property, including digital devices.

All in all, it’s very stressful, especially after a long international flight, when you’re eager to get out of the airport as fast as possible. But that doesn’t mean you have to give up your privacy right away. A better way would be to prepare in advance, and that’s exactly what this post is about.

2. Digital searches never happen at first-line check

The border agent you see first thing on arrival does a so-called first-line check. If everything seems all right, you’re allowed entry and that’s that. But if something about you looks suspicious, the agent will send you to the second-line check — and this is where your property, including digital devices, may be searched.

Therefore, if you want to avoid digital searches (as well as other searches) it’s a good idea to avoid second-line checks. Of course, it’s not totally up to you, but at least you can do your best not to look suspicious. Some typical triggers that may cause a secondary check are:

- Communication difficulties;

- Irregularities in documentation;

- Database signals or database mismatches with your paper documents (for example, the wrong dates or a different spelling of your name on your travel visa).

So before travelling, make sure your documents are in order. Prepare to show the border agent any additional papers you may be asked for (return tickets, hotel bookings, and such). At the border, be polite, calm, confident, and ready to explain where you are going and why, when you’re planning to return home, and so on.

3. Digital searches don’t happen very often

Even if you are sent to second-line check, that doesn’t necessarily mean your devices will be searched. Numbers vary greatly for the largest European airports, from just 7% at Frankfurt to 48% at Paris Charles de Gaulle. In any case, there’s a good chance that second-line screening will be limited to an interview and an additional documents check.

All in all, although the number of digital searches is steadily increasing, they still don’t happen very often. For example, in the US, the number of media searches at borders has grown from 4,764 in 2015 to 23,877 in 2016 and an estimated 30,000 in 2017, but that’s out of about 400 million total border crossings per year, or about 1 in 13,000.

4. Lying to border agents is not recommended — and don’t even think about getting physical

Lying to border agents is a crime in most countries. Probably not something to try. On top of that, if you’re exposed in a lie, the odds of your device being searched skyrocket. With that said, the lie that you can’t unlock your phone because you forgot your password is not a particularly clever or original one.

Trying to interfere physically with border agents searching through your stuff is probably the worst course of action: They are well trained, and the consequences would not be nice.

5. Agents may have some tricks up their sleeves

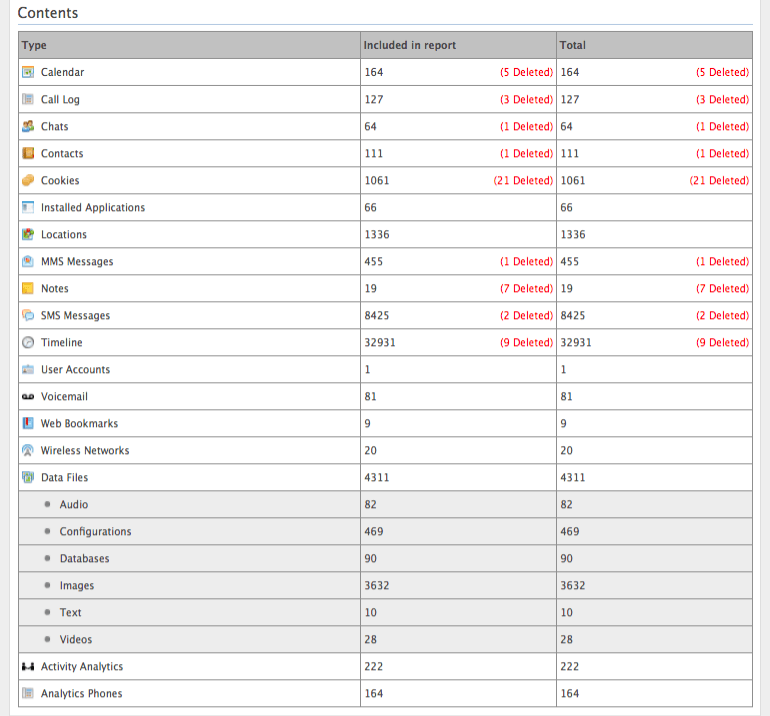

Border agents may have special equipment for quick and effective extraction of data from mobile devices. The most notable examples are devices made by Cellebrite that can extract even deleted information. At least in some cases, this equipment can extract data even from locked devices.

Note that Cellebrite software shows even deleted entries from a phone’s call history, contacts, text messages, and so on

6. Fingerprints are weaker than passwords

Passwords are somewhat protected by the right to remain silent (not ultimate protection, but it’s better than nothing), but fingerprints are not. Therefore, it’s easier for border agents to order you to unlock a fingerprint-protected device than a password-protected one.

Moreover, border agents don’t actually have to ask for your fingerprint: They can just grab your finger and unlock your device. Additionally — although this is extraordinarily unlikely for the average traveller — if they have your fingerprints in a database, they can unlock your devices with a forged copy.

The best way to ensure that won’t happen is this: Enable Full Disk Encryption (FDE) in your operating system and switch off the device before you get to the border. You will be prompted to enter your password when you switch on the device, even if you normally use a fingerprint to unlock the screen. And using FDE is a good practice anyway.

7. People who are searched should document everything — and change their passwords

If you’re searched, write down every detail: what agencies were involved, the names of the agents, badge numbers, what you were ordered to do, and so on. If any of your property is seized, get a receipt.

After the encounter, immediately change any passwords you gave up to border agents. A good password manager can make this part a lot easier for you by creating strong, random passwords and storing them for you.

8. Cloud data is probably better protected than local data

Nowadays, we are used to privacy being ruined on a daily basis by government agencies sniffing around the cloud while not doing much to data stored locally on your devices. But when you’re crossing a border, data in the cloud is likely to be better protected than data stored in device memory. At least, that’s the case in the US. Border agents can search your device and data stored on it, but they don’t have the right to search your data stored in the cloud.

9. Work devices probably fall under employer policies

Find out if your employer is OK with you taking your work devices over a border — and with the possible consequences of a digital search. Make sure you bear no responsibility in case such consequences, which could include corporate data loss or a data leak, take place. Consider leaving work devices at work if you don’t really need them with you.

10. The best solution is not to bring your devices or data

Consider leaving behind not only your work devices, but personal devices as well. If you don’t have the devices on you, there’s nothing to search. However, having no devices at all can look very suspicious to border agents, so one solution would be to bring temporary devices.

The same goes for your data: Don’t bring it with you if you don’t really need it. Store the data in the cloud, but do so securely: Either use cloud storage that supports client-side encryption (unfortunately, most popular service providers do not, but we have a guide on the services that do) or encrypt the data before uploading.

11. Data safety is never guaranteed

Back up all of your data before travelling. Use strong passwords for every service or app and log out of the services before crossing any borders. It should go without saying that you need to protect your devices’ operating systems with good passwords as well. As a bonus, these measures will help you if your device gets stolen which is more likely when you travel than at home.

Delete any data that you don’t need or that might raise questions at your destination (photos that might not matter at home but would be problematic in other countries, for example — showing a lot of skin, say, or drug use). Keep in mind that when you simply delete files, they are not really erased from the disk, so delete data securely.

Deleting files securely is quite easy on laptops — you have plenty of options here, including plain and simple disk formatting (but keep in mind that you have to perform a “low-level format,” not a “quick format”), or special utilities that are available for all desktop operating systems. For example, BleachBit wipes files and can clean browser and recent document history as well as somewhat obscure things like thumbnails (yep, these tiny previews of your files can persist even after the files are deleted).

Secure deletion on mobile devices is a lot trickier, but still possible: Enable Full Disk Encryption and then wipe the encryption keys, making data nondecryptable. This operation is built into factory reset in iOS and in the “power wash” function on Chromebooks (unfortunately, it’s not available in Android).

To learn more, I recommend watching the whole talk by Kurt Opsahl and Daniel Wegemer. It contains a lot of additional nuance, both legal and technical.

34c3

34c3