Cybercriminals are constantly on the lookout for new ways to attack companies. In the past few years, they have increasingly resorted to business e-mail compromise (BEC) attacks that target corporate correspondence.

The US Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) alone reported 23,775 such incidents to the FBI in 2019 — an increase of 3,500 from 2018, plus a rise in damages from $1.2 billion to $1.7 billion.

What is a BEC attack?

A BEC attack is defined as a targeted cybercriminal campaign that works by:

- Initiating an e-mail exchange with a company employee, or taking over an existing one;

- Gaining the employee’s trust;

- Encouraging actions that are detrimental to the interests of the company or its clients.

Usually, the actions relate to transferring funds to criminals’ accounts or sending confidential files, but not always. For example, our experts recently encountered a request that appeared to come from a company’s CEO, with instructions to send gift card codes in text messages to some phone number.

Although BEC attempts often employ phishing-style tricks, the attack is somewhat more sophisticated, with one foot in technological expertise and the other in social engineering. Moreover, the techniques used are one-of-a-kind: The messages contain no malicious links or attachments, but the attackers try to trick the mail client, and thus the recipient, into considering the e-mail legitimate. It’s social engineering that has the starring role.

A careful harvesting of data about the victim typically precedes an attack; the perpetrator later uses it to gain their trust. The correspondence may consist of as few as two or three messages, or it can last several months.

On a separate note, multistage BEC attacks, which combine various scenarios and technologies, are worth mentioning. For example, cybercriminals might first steal the credentials of an ordinary worker using spear phishing, and then launch an attack against a higher-ranking employee of the company.

Common BEC-attack scenarios

Quite a few BEC-attack scenarios already exist, but cybercriminals are forever inventing new ones. According to our observations, most cases are reducible to one of four variants:

- Fake outside party. The attackers impersonate a representative of an organization that the recipient’s company works with. Sometimes it is a real company that the victim’s firm actually does business with. In other cases, the cybercriminals attempt to dupe gullible or inattentive victims by pretending to represent a bogus company.

- Instructions from the boss. Here, the cybercriminals create a fake message in the name of a (usually high-ranking) manager using technical tricks or social engineering.

- Message from a lawyer. The scammers write to a high-ranking employee (sometimes even the CEO) urgently and, above all, confidentially demanding funds or sensitive data. Often, they impersonate a contractor, such as an external accountant, supplier, or logistics company. However, most situations that require an urgent and confidential response are of a legal nature, so the messages are usually sent in the name of a lawyer or law firm.

- E-mail hijack. The intruder gains access to the employee’s mail, and either issues an instruction to transfer funds or send data, or starts up a correspondence with those authorized to do so. This option is especially dangerous because the attacker can view messages in the outbox, making it easier to imitate the employee’s style of communication.

BEC-attack techniques

BEC attacks are also developing from a technological point of view. If in 2013 they used the hijacked e-mail accounts of CEOs or CFOs, today they rely increasingly on successfully imitating another person through a combination of technical subterfuge, social engineering, and inattentiveness on the part of the victim. Here are the basic technical tricks they employ:

- E-mail sender spoofing. The scammer spoofs the mail headers. As a result, for example, a message sent from phisher@email.com appears to come from CEO@yourcompany.com in the victim’s inbox. This method has many variations, and different headers can be changed in various ways. The main danger of this attack method is that not only attackers can manipulate message headers — for a variety of reasons, legitimate senders can do it too.

- Lookalike domains. The cybercriminal registers a domain name that is very similar to the victim’s. For example, com instead of example.com. Next, messages are sent from the address CEO@examp1e.com in the hope that a careless employee will fail to spot the fake domain. The difficulty here lies in the fact that the attacker really does own the fake domain, so information about the sender will pass all traditional security checks.

- Mailsploits. New vulnerabilities are always being found in e-mail clients. They can sometimes be used to force the client to display a false name or sender address. Fortunately, such vulnerabilities quickly come to the attention of infosec companies, allowing security solutions to track their use and prevent attacks.

- E-mail hijacking. The attackers gain full access to a mail account, whereupon they can send messages that are almost indistinguishable from real ones. The only way to automatically protect against this type of attack is to use machine-learning tools to determine the authorship of the e-mails.

Cases we’ve encountered

We respect the confidentiality of our clients, so the following are not real messages but examples that illustrate some common BEC possibilities.

False name

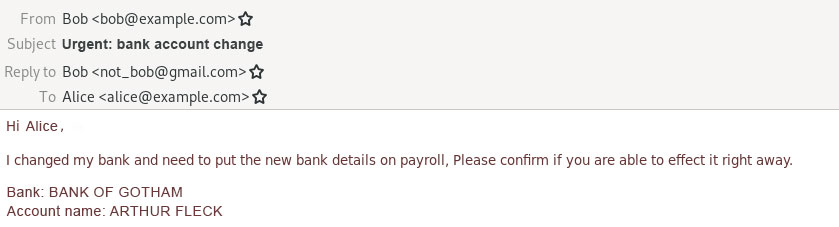

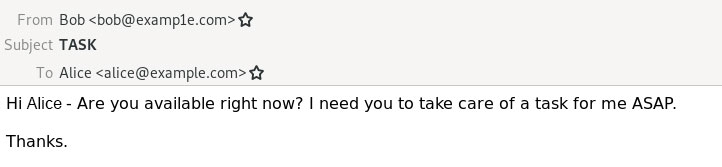

The attacker tries to establish contact with a potential victim, posing as their boss. So that the recipient does not try to contact the real senior officer, the scammer highlights both the urgency of the request and the boss’s current unavailability through other communication channels:

A close look reveals that the name of the sender (Bob) does not match the real e-mail address (not_bob@gmail.com). In this case, the attacker faked only the name displayed when the message is opened. This type of attack is especially effective on mobile devices, which by default display only the sender’s name, not their address.

Fake address

The cybercriminal seeks out an employee in Accounting who is authorized to alter bank details, writing:

Here, the message header is changed so that the client displays both the name and the e-mail address of the legitimate employee, but the attacker’s e-mail is given as the reply-to address. As a result, replies to this message are sent to not_bob@gmail.com. Many clients hide the reply-to field by default, so this message appears genuine even on close inspection. In theory, an attack using such a message could be stopped by correctly configuring SPF, DKIM, and DMARC on the corporate mail server.

Ghost spoofing

The attacker, pretending to be a manager, impresses upon the employee the need to cooperate with a bogus lawyer, who will supposedly soon be in touch:

Here, the sender field contains not only the name, but also the spoof e-mail address. Not the most cutting-edge technique, but still many people fall for it, especially if the real address is not displayed on the recipient’s screen (for example, simply because it is too long).

Lookalike domain

Another cybercriminal tries to start up an e-mail exchange with a company employee:

This is an example of the lookalike-domain method, which we mentioned above. The scammer first registers a domain name similar to a trusted one (in this case, examp1e.com instead of example.com), and then hopes the recipient doesn’t notice.

High-profile BEC attacks

A number of recent news reports have highlighted BEC attacks causing significant damage to companies of various shapes and sizes. Here are a few of the most interesting:

- A cybercriminal created a domain mimicking that of a Taiwanese electronics manufacturer, and then used it to send invoices to major companies (including Facebook and Google) over a period of two years, pocketing $120 million in the process.

- Pretending to be a construction firm, cybercriminals persuaded the University of South Oregon to transfer nearly $2 million to accounts controlled by scammers.

- Some fraudsters meddled in correspondence between two soccer clubs by registering a domain containing the name of one of them but with a different domain extension. The two clubs, Boca Juniors and Paris Saint-Germain, were discussing the transfer of a player and the commission on the deal. As a result, almost €520,000 went to various fraudulent accounts in Mexico.

- Toyota’s European arm lost more than $37 million to cybercriminals as a consequence of a fake bank transfer instruction that an employee mistook for legitimate.

How to handle BEC attacks

Cybercriminals use a fairly wide range of technical tricks and social-engineering methods to win trust and carry out fraud. However, taking a range of effective measures can minimize the threat from BEC attacks:

- Set up SPF, use DKIM signatures, and implement a DMARC policy to guard against fake internal correspondence. In theory, these measures also permit other companies to authenticate e-mails sent in the name of your organization (assuming, of course, that the companies have those technologies configured). This method falls short in some ways (such as not being able to prevent ghost spoofing or lookalike domains), but the more companies that use SPF, DKIM, and DMARC, the less wiggle room cybercriminals have. Use of these technologies contributes to a kind of collective immunity against many types of malicious operations with e-mail headers.

- Train employees periodically to counter social engineering. A combination of workshops and simulations trains employees to be vigilant and identify BEC attacks that get through other layers of defense.

- Use security solutions with to defeat many of the attack vectors described in this post.

Kaspersky solutions with content filtering specially created in our lab already identify many types of BEC attacks, and, our experts continually develop technologies to protect further against the most advanced and sophisticated scams.

BEC

BEC

Tips

Tips